Health researchers in Australia have revealed how stress can turn the body’s lymphatic system into a super highway for breast cancer cells, thus allowing the cancer to spread more rapidly.

Research study shows cancer spread faster in stressed mice

Medication was used to prevent the effect of stress on cancer in mice

A study is being planned on stress in human cancer patients

For the time being, scientists also know how to prevent it from happening, in mice.

The medical community has long debated how stress affects a patient’s prognosis, and while stress has not been proven to cause cancer, scientists now say it might have a significant role in how it spreads.

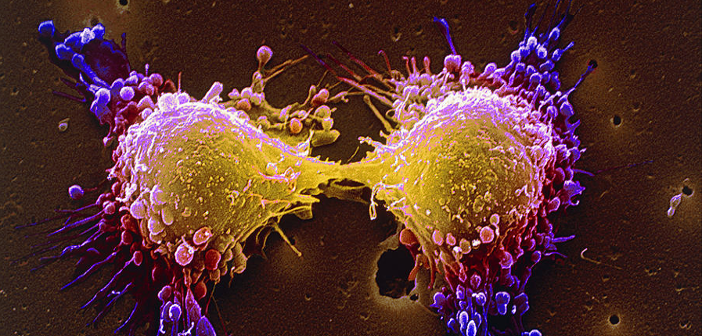

A research team from Monash University led by cancer biologist Dr Erica Sloan studied how stress drives metastasis — the spread of an existing cancer from the original tumour — in mice with breast cancer.

According to Dr. Sloan, “Stress sends a signal into the cancer that allows tumour cells to escape from the cancer and spread through the body.”

“The stress is sort of acting like a fertiliser and helping the tumour cell take hold and colonise those other organs.”

Dr Sloan said although it was already known cancer could spread through the lymphatic system, her team discovered stress transformed the network into a super highway that allowed the cancer cells to travel at much faster speeds.

The research team placed mice with cancer in confined spaces in order to mimic the physiological and emotional effects of stressed humans.

Dr Caroline Le, who was part of Dr Sloan’s team, said the effect the stress had on their cancer was marked.

“You see six times more spread of cancer in stressed mice compared to control mice,” she said.

Stress Medication in mice

Stress levels typically increase in a patient after a cancer diagnosis.

The good news is Dr Sloan’s research team found an age-old class of medication — currently used for high blood pressure and cardiac arrhythmia — could prevent the stress facilitating the cancer’s spread.

The medication contains beta blockers which prevent the stress response by competing with adrenalin to limit heart rate and blood pressure increase.

When the beta blockers were given to the mice with cancer, the stress response was completely negated. The stress no longer restructured the lymphatic system that led to the increased cancer spread.

Treatment in humans

A human pilot trial is currently being conducted by anaesthetist Dr Jonathan Hiller at the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne. His trial is focusing on anxiety in female surgical patients recently diagnosed with breast cancer.

“We’ve chosen the peri-operative period because, as an anaesthetist, we often see women have a state of increased stress and anxiety at the time of surgery, and the build-up to surgery following diagnosis can be incredibly anxiety provoking,” Dr Hiller told Catalyst.

In his double-blind trials, patients are being given either the beta blocker Propanolol or a placebo, and their stress levels before and after surgery are being recorded via blood samples.

Stress signatures which are present in white blood cells are being analysed to see if the beta blocker can change the stress signatures at the time of surgery.

The ground-breaking study is still ongoing, but depending on the results of the trial, researchers may be able to develop a cancer-specific beta blocker that is designed to target tumours, not the heart.