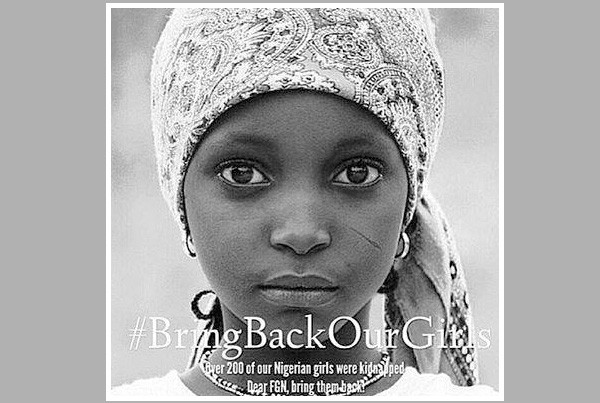

Only months ago, the mass kidnapping of 276 schoolgirls in a school in Chibok transfixed Nigeria and sparked a hashtag, #BringBackOurGirls. Now, as President Goodluck Jonathan seeks a second term, it barely even registers as a campaign issue.

Neither President Jonathan, who had vowed to “not sleep with my two eyes closed until these girls are brought safely back with their parents,” nor his rival, former military leader Muhammadu Buhari, have spent much time talking about the girls in stump speeches. They appear to be taking their cues from ordinary Nigerians—voters polled tend to complain about corruption, joblessness and daily blackouts far more than the students’ fate.

And yet every afternoon, a dwindling corps of protesters, a fraction of the crowd that used to gathe, still shuffles onto a highway median to once more remind Africa’s largest democracy that 219 of those girls remain missing. This week, on the 301st day of their captivity, about 40 demonstrators held their daily vigil on the grass under a banner that read “Bring Back Our Girls.” “Even my own people have given up,” said Victor Ibrahim Garba, a protest leader who represents the girls’ families. Many of the parents, he added, now want the air force to bomb the forests where Boko Haram is likely keeping their daughters. “People are saying bring back the dead bodies so that we can bury our dead.”

Nigeria, Africa’s biggest economy and most populous country has seen such a litany of bad news in the past year that its most famous case of missing people now ranks as a distant preoccupation. With the country’s currency crashing, its oil revenue collapsing, its election heating up and Boko Haram slaughtering villagers daily, many here see the schoolgirls as a distraction or even an invention made up to embarrass the president.

On Wednesday, about 20 more boys and girls were taken from the tiny village of Akada-Banga, residents there said. Later on that day, President. Jonathan spent three minutes in an 80-minute presidential chat to discussing the schoolgirls, at one point saying the protesters “try to play politics with the case of the Chibok girls.” “Is it by bringing flags and singing around the world that we will bring these girls?” he added. “Just give us some time.”

In the 10 months since the girls’ disappearance from Chibok, about 10,000 people have died in Nigeria’s Boko Haram conflict, representing about half of the Nigerians killed over the past four years, according to New York’s Council on Foreign Relations. Some 1.5 million have been displaced and hundreds, with perhaps thousands more boys and girls kidnapped.

Chibok is empty, among the scores of abandoned towns Boko Haram has torched and looted.

In the six years Nigeria’s military has battled Boko Haram, the insurgency has shifted from carrying bows and arrows to firing antiaircraft weapons and driving armored personnel carriers stolen from the army. By the end of last year, the group had seized a considerable swath of Nigeria.

Meanwhile, there are pocketbook issues on the minds of many voters and candidates in this election, which is shaping up to be the closest in Nigerian history. The falling price of oil has dried up government revenue in this crude-exporting country. The stock market is collapsing, some civil servants haven’t been paid, and the currency is trading at record lows.

Hours before the regular Chibok demonstration, a crowd of President Jonathan’s supporters several times larger had filled the same median. As that group amassed to pass out fliers and soda to the public, many said they still didn’t believe Boko Haram actually drove into a school in April 2014 and sped away with more than 200 female students. “It’s a gimmick,” said Natty Vince, a consultant, echoing the disbelief of many Nigerians who doubt how the Islamist insurgency could fit such a large number of girls into its pickup trucks. “There is certainly no proof,” said Chris Ebosie, a management consultant. “They are not the only girls” who have been held hostage in Nigeria, he added.

Amid these doubts, and the prospect of getting drowned out in a noisy presidential campaign, a few dozen demonstrators still meet each afternoon on the same highway strip to mark the number of days since the schoolgirls went missing.

“Welcome to day 301 of our Chibok girls’ abduction and 286 of our daily sit-out,” said Maureen Kabrik on Monday afternoon. The group discussion began with a grim announcement of the latest attacks up north. A town on the Niger border had been bombed. Boko Haram’s leader, Abubakar Shekau, had released another video threatening to wage war across West Africa. One protester borrowed the microphone to describe an 11-year-old girl she had seen in a documentary, living as a refugee in Cameroon. The girl hadn’t eaten for three days, she said.

“And this is someone my daughter’s age,” said Aisha Yusufu, breaking into tears. “And nobody bothers!” A pair of women walked over to console the weeping mother. “As you can see,” said the group’s leader, Obi Ezekwesili, “we are still here.”

Source: The Wall Street Journal