A new research study has revealed that a gene mutation in human in West Africa thousands of years ago gave them immunity to malaria and also gave some of their descendants to sickle cell anaemia.

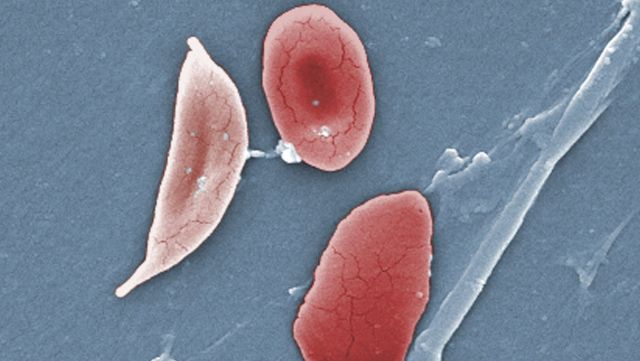

Sickle cell anaemia is prevalent in Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and India, and many of these babies are likely to die from the disease in which their red blood cells break apart, leaving their bodies starved of oxygen. It is caused by two copies of a gene mutation in their DNA. One copy is harmless; two copies can be deadly.

Millions of people worldwide, most especially those with African heritage, are carriers of this mutant gene, but there are large gaps in our knowledge of the disease and its characteristic mutations.

According to WHO, sickle cell anaemia is responsible for 5% of deaths of under-five-year-old children on the African continent, with more than 9% of such deaths in West Africa, and up to 16% of under-five deaths in individual west African countries.

The new research shows the disease began with a single genetic mutation in a child born about 260 generations ago. Human DNA contains two copies of this gene, and when only one copy contains the mutation, carriers are better able to fend off malaria, something which was vital for survival on the African continent.

But two copies of the mutation cause sickle-cell anaemia, in which a person’s red blood cells are not shaped like disks (as they are in healthy people), but like the sickle moon.

The new research, published in scientific journal Cell, has found that this disease began with a single ancestor who developed the mutation to fend of malaria.

Daniel Shriner and Charles Rotimi, researchers at the Center for Research on Genomics and Global Health, in National Human Genome Research Institute in the United States, surveyed about 3,000 genomes, drawing on data from the 1000 Genomes Project, the African Genome Variation Project, and Qatar. They identified 156 carriers of the genetic mutation, and by analysing the DNA surrounding the mutation found evidence for a shared ancestor.

“Our results indicate that the origin of the sickle mutation was in the middle of the Holocene Wet Phase, or Neolithic Subpluvial, which lasted from 7,500–7,000 BC to 3,500–3,000 BC,” the authors write. The Green Sahara periods, as this was known, would have meant that the environment would have been lush, and an ideal habitat for the malaria mosquitoes.

“An alternative hypothesis is that the sickle allele [mutation]arose in west-central Africa, possibly in the northwestern portion of the equatorial rainforest.”