You surely must have heard of HIV/Aids but i doubt if you’ve heard of Francoise Barre-Sinoussi. She was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine for her pioneer role in the fight against the human immunodeficiency virus, HIV scourge.

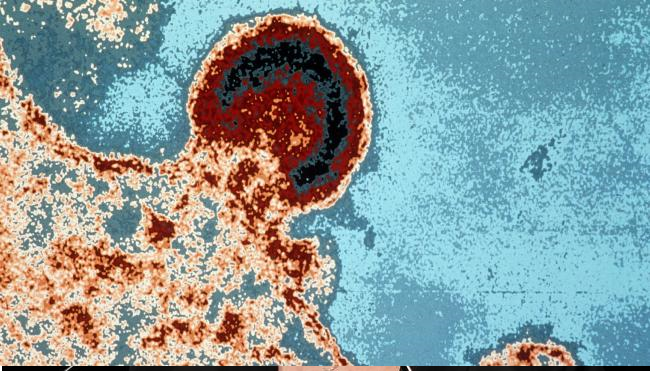

It took Ms Barre-Sinoussi just two weeks to uncover the cause of AIDS after being set the challenge in early 1983. Beavering away at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, to find what is now one of the world’s most well-known viruses — HIV.

The discovery of HIV changed medical science, but it had a tragic side effect — it gave false hope to desperately ill people looking to cling onto life. “People who were affected by the disease were coming directly to Paris asking the obvious question: ‘When are you going to have a treatment for us?’” Ms Barre-Sinoussi said.

“They were in a very bad shape. Less than 30, they were thin, and their faces looked very old even though they were young. Some died a few days after. “It was a terrible period because we had no solution. As scientists, we knew it would take years, but as human beings we thought if we don’t do something rapidly they will die.”

Ms Barre-Sinoussi was so affected by it all, that those closest to her had to intervene. “I was going to restaurants, telling my husband ‘I’m sure this guy over there has HIV’ and I remember him telling me, ‘please stop, you are becoming crazy’.”

Ms Barre-Sinoussi is in Durban, South Africa, for the biannual global AIDS conference. A former head of the International AIDS Society (IAS), Ms Barre-Sinoussi has been spearheading efforts into finding a cure for the disease.

AIDS was first discovered in 1981 and was originally thought to be a “gay cancer” but it soon became clear the disease did not discriminate. In 1983, Ms Barre-Sinoussi’s team worked out that HIV — or the human immunodeficiency virus — was invading the very cells that should have fought off the infection.

With their immune systems shot, people would eventually get AIDS and fall sick from illnesses any healthy person could fight off. Brain infections, cancers and teeth and hair falling out were common stages on the road to death.

Modern treatments have been so effective in Australia there have even been recent suggestions that “the age of AIDS is over”. Nonetheless, 1000 people get HIV each year in Australia but this pales into insignificance compared to the 2500 women who get HIV every week in sub-Saharan Africa.

What is needed is a cure and Ms Barre-Sinoussi has been helped with that task by Professor Sharon Lewin, who leads a global HIV research hub at Melbourne’s Doherty Institute. With the French virologist stepping back from front-line research, she said she hopes Ms Lewin would be her “clone” continuing the fight against HIV.

“She’s quite an extraordinary woman. But I can’t be Francoise,” she said in Durban. “She is like the mother figure of HIV, the Madonna, in a religious sense, and we would not have had as much prominence around searching for a cure without Francoise. “No one was talking about a cure until Francoise came along. The shorter term goal was just to make sure people didn’t die.”

Ms Lewin first began her studies into HIV in the early 1990s when there were no treatments even in Australia. “I remember this young man who got sick very quickly, he hadn’t told his family and died alone.”

While Ms Lewin and her US colleague Professor Steve Deeks will continue the work to find a cure, she said remission was a more likely outcome at first.

“People talk about finding a cure for cancer but there are many cancers that can’t be cured and what doctors are looking for is remission which is analogous to HIV,” she said.