According to mainstream women’s magazines, there are about as many types of female orgasms as there are brands of flattering workout pants. There’s the storied g-spot orgasm, the cutting edge “a-spot” (“anterior fornix”) orgasm, the even more obscure “u-spot” (urethra) orgasm, the cringe-y sounding cervical orgasm, and for boring underachievers, the basic and accessible clitoral orgasm. Scientifically speaking, though, just how many orgasms are there?

There’s no consensus yet from the medical community, in part because there’s disagreement about how to define an orgasm in the first place. Some researchers and sexperts favor a definition like the one sex educator Emily Nagoski provided in last year’s best-selling Come As You Are: “Orgasm is the sudden, involuntary release of sexual tension,” a description that carefully omits mention of concrete physical markers. For others, like neuroscientist and psychophysiologist Nicole Prause, identifying a physical response is key. Knowing what, exactly, an orgasm is seems like a reasonable basis for determining where it originates and ultimately manifests — the apparent mission of proselytizers of increasingly elaborate orgasm types. What else are they trying to put a name to?

In their efforts, they’re honoring — you guessed it — good old Sigmund Freud, who popularized the bifurcation of women’s sexual response into clitoral and vaginal over a century ago. Thanks to second-wave feminism, it’s widely accepted that his theory left a legacy of collective psycho-sexual baggage we’ve barely begun to slough off, but even he couldn’t have anticipated the climax cottage industry that his dubious claims about “sexual maturity” ushered in. If you’ve got the genitalia of a cis woman — meaning a vulva, a vagina, a clitoris, a cervix, and all the rest — you should, according to some experts, be able to “achieve” up to 10 different varieties of sexual release through skillful manipulation of your myriad private parts. But the best evidence suggests bodies simply don’t work like that.

Let’s start with the fact that the vagina and clitoris are intimately connected to the point of near inextricability — and that’s not news. In 1966, Masters and Johnson excoriated the suggestion that they’re distinct.

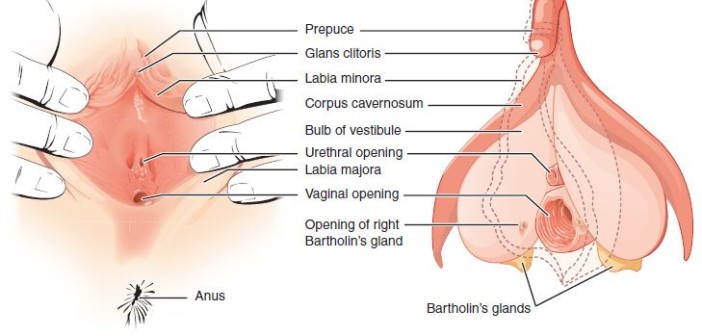

Vaginal and clitoral orgasms are not separate because the vagina and the clitoris, as anatomical structures, are not separate. Bodies are not assembled as cleanly as plumbing systems, in spite of what common parlance for our reproductive systems suggests. As one 2005 paper notes, “The anatomy of the clitoris has not been stable with time … To a major extent, its study has been dominated by social factors.” By today’s best evidence, derived from meticulous cadaveric dissection, it is an organ that extends deep into the body on multiple planes, and constitutes far more than the small glans and hood that most of us think of as “the clit.” When recognized in its complete, three-dimensional glory, it has something of a wishbone shape and comes into contact with the labia, urethra, mons, and vaginal walls.

Because of its location against the top wall of the vagina, around the urethra, and along the labia, stimulation and pressure on any of these adjacent areas during sex necessarily applies pressure, friction, vibration, and so on, to the clitoris. “It is therefore problematic at best to define a ‘clitoral orgasm’ as a phenomenon distinct from a ‘vaginal orgasm,’” declared one intensive medical review from 2015.

Legendary sex educator Betty Dodson is particularly vehement on this point. “An orgasm is an orgasm is an orgasm!” she said, while lamenting our continued preoccupation with “vaginal” orgasm. “The clitoral body is the primary source of orgasm whether it’s stimulated externally, internally, or both.” “If something is put into the vagina, the clitoris is always displaced.” In most cis women’s bodies, you can’t stimulate a vagina without stimulating the clitoris at the time, Nicole Prause emphasized.

Internal structure of the clitoris aside, the external, visible portion of the clitoris (the glans) is also influenced by penetration, as plenty of sex position manuals indicate. Women who come from penetration without targeted manipulation of their glans may experience external clitoral stimulation through penetration regardless, due to general friction in that same area. Furthermore, pulling on the skin at the vagina’s vestibule results in some stretching of the glans and clitoral hood as well the vascular tissue of the urethra. (Our beloved u-spot!) The interwoven nature of these tissues is the cause of “ambiguity problems” when trying to identify the source of orgasm — but it’s only a “problem” if ideological values demand the artificial deconstruction of a body’s holistic, quirky functioning. The very structure of genitals renders orgasm parsing impossible.

So what is an orgasm then, this experience that can’t be pinned to a specific hodgepodge of genital triggers? Anatomically, “an orgasm consists of highly stereotyped contractions, which means they always occur in the same type of pattern,” says Prause. “It’s 8 to 12 contractions that start about 0.8 seconds apart and increase in latency until they stop.” It’s a pretty straightforward take that’s easy for researchers to verify in a subject — which can’t be said for Nagoski’s definition, mentioned above. (“Orgasm is the sudden, involuntary release of sexual tension.”)

Nagoski’s stance prioritizes self-reporting over observable and quantifiable physical indicators, and doesn’t even mention genitals. Given how commonly women evince arousal noncordance— how often their bodies indicate arousal without being accompanied by a subjective sense of feeling turned-on, or vice versa — it’s understandable that this approach is generally positioned as the more feminist or otherwise women-friendly option. (Men also experience discordant arousal pretty frequently, but not as regularly women do.)

But like Nagoski, Prause’s framing leaves plenty of room for subjective experience. An orgasm can fit both or either set of criteria yet be disappointing, unsatisfying, or not particularly powerful — something magazine articles rarely address when they’re exhorting their audience to go O wild. An orgasm is not guaranteed bliss; quality varies. But it’s hard to psych readers up for digging around in their anterior vaginal walls for 30 minutes, chasing an elusive experience that may prove underwhelming once obtained. Better to promise “new heights” of pleasure. If you can find the right spot, and leave it at that, any experience less than sheer ecstasy will seem like the fault of the body in question.

Nagoski and Prause share something else in common in spite of divergent approaches to climax: both believe that orgasm is, essentially, a singular experience — meaning there is no “kind” or “type” of orgasm, only different ways of inducing it.

Some people base it on where the stimulation comes from,” explains Prause, which is why articles about “nipple orgasms” and “anal orgasms” exist, but “there’s no physical evidence that supports the idea of different types of orgasm.” No matter how they’re induced or what part of the body seems to be receiving the most stimulation, orgasms result in those stereotypical contractions. For a researcher like Prause, a so-called g-spot orgasm is indistinguishable from a so-called clitoral orgasm.

We can glare back at Freud when looking to understand why our culture is so obsessed with detailing something that doesn’t exist (i.e., sexual climaxes that stem from different sources). The preoccupation with orgasm through vaginal penetration alone — and the quest to induce it in every woman — opened a Pandora’s box of possibilities for segmenting women’s genitals into discrete components with separate sensations and capacities. Lady privates, notoriously complicated as they are, have become regarded as a collection of parts before — if not altogether instead of — a cohesive whole. Our culture already sends women on a fruitless chase for pleasure in an area of their body not as fully primed to provide it as others, so why not add new zones to the list? If you’re diligently trying to engage a vagina without any clitoral side effect, why not try stroking the urethral opening (without touching the clitoris, because that’s sensible) while you’re at it? As an aside: how hell-bent are you people on getting or giving a UTI?

This is the inverse of how we generally think and talk about men. “Penis” indicates an area of widely varying sensitivity and nerve distribution, but somehow this fact doesn’t inspire a mountain of articles on, say, how to get a guy off by stroking only the base of his shaft or petting his urethral opening. Mercifully, some academics are working to reverse this trend. One 2012 study, for instance, concluded that the “specialized tissues” of the vulva show a “unified response to sexual arousal.” (The paper opens with the endearing complaint that “the anatomy of the vulva is typically presented with no unifying theme.”) But the sanest voices in this discussion are drowned out by a sexist, sex-crazed pop culture with little to no interest in real anatomy.

There’s nothing wrong with exploring one’s body for different types and degrees of pressure, but the overbearing cultural imperative for women to do so, with its transparent sociopolitical agenda, is a problem. The next time a person, daytime TV segment, or magazine article tries to imply you’re inferior because you don’t experience 12 different types of orgasms, remind yourself that they’re advocating the impossible, and looking pretty silly while they do it.